Rutgers student criticizes University after sexual assault

The Case

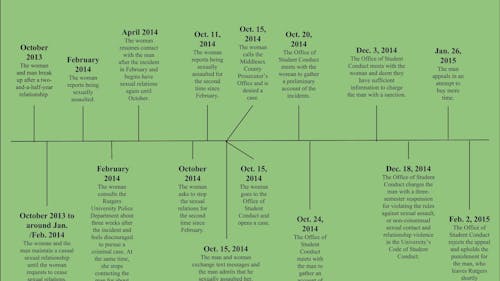

After she was sexually assaulted twice on campus in a year, a Rutgers student is voicing disbelief about how her incident was handled by the University’s Office of Student Conduct when her offender, a former boyfriend, was reprimanded with a three-semester suspension instead of the expulsion she felt he deserved.

According to documents amassed by Rutgers investigators during the case and provided to The Daily Targum by the woman who requested anonymity, the sexual assaults occurred and were reported in February 2014 and October 2014.

The suspended student, who also requested anonymity, supported the validity of the documents in a phone interview with The Daily Targum in early March.

The University declined to speak about the specific case in compliance with the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act in an interview with The Daily Targum in late February, but addressed the way reports of sexual assault are handled with the Code of Student Conduct and Title IX.

The two individuals said they had dated for two-and-a-half years until their breakup in October 2013 but maintained a casual sexual relationship until around January or February 2014.

A few weeks later, the woman reported being sexually assaulted by the man in her apartment where he continued to touch her as she said she repeatedly said “no.” During this incident and in the incident that followed in a number of months, neither individual was under the influence of drugs or alcohol.

“What happened in February was rape,” the woman said. “(He) and I talked about it, but it did not become real to me at that point because neither of us used the word ‘rape.’ He expressed how sorry he was and how he felt ‘out of control’ and did not know what was wrong with him.”

The woman stopped contacting the man for several weeks after the incident and contacted the Rutgers University Police Department about three weeks later, where she said Rutgers police officers told her how long the process could be and that it could take several years to bring about a prison sentence. When the woman coupled what the officers said with the low national rates of conviction for sexual assault perpetrators, she felt discouraged and stopped pursuing criminal charges until October.

“I could attempt to get a restraining order, but it felt so discouraging to know nothing could be done,” she said. “I convinced myself that it simply was not a big deal because if the legal system could do nothing, then clearly nothing had been that bad.”

Although the woman did not pursue the case through the criminal process, University spokesperson E.J. Miranda said Rutgers police strongly encourages anyone who believes he or she was a victim of a crime to report the incident to school law enforcement.

Under the Code of Student Conduct, students can choose to consult the criminal system and Rutgers' conduct process prior to, simultaneously or following civil or criminal proceedings. Students can also choose to only utilize one or neither channel.

“RUPD treats victims with respect, courtesy, and dignity, believing that a victim's safety and privacy are of major importance,” he said. “Filing a report does not commit an individual to pursuing an investigation or prosecution and the police will respect the victim's decision.”

Around the same time when the woman consulted the police, she said one of her former roommates who knew about the incident advised her not to press charges against the man for risk of “ruining his life.”

“I felt like clearly I was overreacting and started to feel as though maybe I hadn’t said ‘no’ enough or since I had not fought back physically despite saying ‘no,’ that he simply had not understood that I did not want to have sex,” she said.

In the weeks after the first incident, the woman said she often felt lonely and scared, and returned to having sex with the man who assaulted because she wanted to feel physical closeness, despite the fact that she was afraid being around him.

The two individuals resumed a consensual sexual relationship for several months, although the woman said the experiences were “horrible” and that she would throw up every time after having sex with him.

“I had relied on (him) for so long that it seemed natural to seek comfort from him,” she said. “However, he raped me, so it was all tremendously f----d up.”

Since then, the two maintained a relationship without having sex until Oct. 11, when she said she slept in his bed with him as she had done several times prior with the mutual understanding that nothing sexual would happen.

During the night, she was awakened by the man rubbing her shoulders who asked the woman within the hour if “she would let him have sex with her,” to which she recalled saying “okay” or nodding her head affirmatively, although she said she nodded more out of a desire to remain compliant. The man avoided eye contact with the woman during intercourse, finished and said “I can’t believe I did that.”

Four days later, on Oct. 15, the woman sent the man a series of text messages around 5 a.m. expressing her disgust and fear at the incident.

“And maybe I will never be able to have a healthy sexual relationship because of you?” she wrote. “Doesnt that seem unfair? (sic)”

The man responded with his own series of texts about three hours later.

“I just destroyed you,” a sentence from one of his texts read. “I raped you.”

The woman said her meeting with Rutgers police in February thoroughly discouraged her but she thought the text message was enough to initiate an investigation so she said she brought a report, this time to the Middlesex County Prosecutor's Office on Oct. 15 with a counselor from the University’s Office of Violence Prevention and Victim Assistance.

She said she asked the Middlesex County Prosecutor to pursue criminal charges and the prosecutor told her that she had no legal case and no chance to press charges against the man.

“I have a written statement from (the man) which says ‘I raped you,’” the woman said. “So I thought naively if I went forward to the police that would be enough … (but) legally, I have no case because I had consensual sex with him at one point.”

That same day, the woman proceeded to open a case with the University's Office of Student Conduct and began working with University administrators Felicia McGinty, Joe DiMichele, Jackie Moran, Jordan Draper and Jon Bouchard.

University Action

In the coming months, investigators found the man responsible for two violations under the Code of Student Conduct: sexual assault, or non-consensual sexual contact, and relationship violence.

Under the code, sexual assault or non-consensual sexual contact is defined as touching a non-consenting person with one’s own intimate parts or penetrating a non-consenting person orally, vaginally or anally with any object or body part through the use of force, threat, intimidation, coercion or exploitation of the person’s inability to consent.

Relationship violence, a distinct violation from sexual assault or non-consensual sexual contact, is any act of physical, sexual or psychological harm against a current or former intimate or romantic partner.

With these violations in mind, administrators decided to readmit the man after a three-semester suspension, allowing him to come back May 2016, or the time when the woman would have already graduated from the University.

“Felicia McGinty, the vice chancellor of Student Affairs, said (suspension) was an appropriate punishment,” the woman said.

Brett Sokolow, founder, president and chief executive officer of the National Center for Higher Education Risk Management and one of the top legal advisors for college sexual assault cases in the United States, saw both sides of the case in a phone interview with The Daily Targum in early March.

“If (the man) committed an act of rape, and by that I mean something very specific, legally, then he absolutely ought to be expelled,” he said. “A three-semester suspension, in my view, would not be appropriate.”

Sokolow, who legally defined rape as “a forcible or non-consensual sexual attack,” said Rutgers reached a gray area with the case because the woman reported rape in February then resumed sexual activity afterwards until October and nodded her head in response to the question “Are you going to let me have sex with you?” in October.

For these reasons, he said he understood the investigators’ thought processes for choosing the sanction.

“There’s a reason why this never gets prosecuted,” he said. “At the moment of the act (the woman) was acting in a way that could be interpreted by some people as consent.”

Consent, as it is currently defined in the Code of Student Conduct, is one of the weaker points in the book, said Anne Newman, chief of staff at Rutgers Student Affairs.

“Right now, we define who cannot give consent as opposed to what consent looks like,” she said. “So as the University moves forward we have to determine for ourselves whether or not this definition is okay or whether or not we have to define consent.”

But in the current moment, with no immediate revisions slated to be made for the Code of Student Conduct, administrators are working to balance the needs of the victim and public with the rights of the perpetrator.

Students who are readmitted back to Rutgers after a period of suspension can still be required to follow certain sanctions when they return to campus, Newman said.

For instance, students can only be readmitted after the victim graduated or when the victim is away on spring break, she said. Other sanctions can mean being allowed to take only online classes or being barred from a particular residence hall.

But even if administrators mandate sanctions when a suspended student returns to campus or expel the student, she said feelings of fear can still persist.

“Even if we expel someone, we can’t make them leave New Brunswick or Piscataway,” she said. “We can only control on the campus, so what we try to do is make sure they have all the resources available to handle what’s going on inside them. We do contact restrictions and monitor those closely.”

In this case, the woman who was assaulted said the investigators leveraged no sanctions for the man when he is allowed to return to campus, and she fears for the safety of other female students on campus in the future.

“It’s a really unsafe environment, and it makes me think how many other young men who have raped women are on campus now,” she said.

Ruth Anne Koenick, director of Rutgers’ Center for Violence Prevention and Victim Assistance, said she thinks the University has a process that works but not everybody will see it that way.

“For every case that we handle, it’s a case-by-case basis,” Newman said. “So we look at the individual incident that occurred, the facts of the case and the information that’s provided by both the accused and the victim for that individual case.”

Although every case is unique, a period of suspension is always the minimum sanction in cases of sexual assault, she said. An expulsion is mandated when investigators find the accused student to be a danger to the University community.

A suspended student would carry a notation on their transcripts that indicates they were suspended for a “disciplinary reason” and not for the specific issue of sexual assault, Newman said. If the student were to transfer to another university, the transfer school would have to directly contact Rutgers to find the details of the student’s violation.

A student who was suspended through the Office of Student Conduct would also not have sexual assault on their criminal records although they would on their academic disciplinary records, Newman said.

“We’re not the criminal process,” she said. “The University process is completely separate from the criminal process.”

With two separate avenues for handling cases of sexual assault, two sets of data exist for each.

More extensive data listed under the 2014 to 2015 Clery Act Report for the University indicated 26 reported sexual assaults to University offices between 2011 and 2013 on all on-campus property, non-campus property, public property and on-campus residential property.

In the same time period and on the same properties, two sexual assaults were reported to University police instead of University offices in 2011, seven in 2012 and five in 2013, Miranda said.

“We don’t have a lot of students that want to go through our process,” Newman said. “So the numbers of sexual assaults that occur are a whole lot higher than the students that actually choose to go through the formal process of filing a University complaint against a student. So our numbers are a whole lot lower than we’d like them to be.”

National Responses

According to findings from The Philadelphia Inquirer in July 2014, from 2010 to 2014, the University judicial board reviewed 12 cases of sexual assault, three of which resulted in expulsion.

The University's numbers for expulsion are largely mirrored in national statistics for a multitude of American universities.

“Students found responsible for sexual assault were expelled in 30 percent of cases and suspended in 47 percent of cases," The Huffington Post found in data collected from nearly three dozen colleges and universities. "At least 17 percent of students received educational sanctions, while 13 percent were placed on probation, sometimes in addition to other punishments.”

In the same data study from September 2014, an analysis of data from more than 125 schools from 2011 to 2013 showed a minimum of 13 percent of students were expelled to a maximum of 30 percent. Conversely, between 29 to 68 percent of students were suspended.

In a similar, more dated vein, data maintained by the United States Department of Justice’s Office on Violence on Women from 2003 to 2008 revealed that colleges rarely expel men found responsible for violating their schools’ sexual assault policies — only 10 to 25 percent of students are prohibited from ever returning, according to a 2010 report from the Center for Public Integrity.

Now What?

With the University process, an investigative report is drafted from meetings with both accused and complaint parties, and investigators determine if charges should be brought against the accused student, Newman said.

The complainant party can assist in establishing repercussions by recommending a sanction, which investigators take into account when making their final decision for the accused student during a hearing, she said.

After the hearing, the accused student can request an appeal to readdress points of disagreement, she said.

In this case, because the man admitted to sexually assaulting the woman via text and confirmed it again to the investigators there was no hearing and the investigators proceeded to find a sanction appropriate to the violations, both the man and woman said.

But after receiving the sanction for suspension on Dec. 18, the man appealed because the investigators’ findings were “unsupported by the evidence,” and that the sanction was “unjust,” according to his written testimony.

“I will also explain that my feelings of emotional guilt, as expressed in the text messages sent to (the woman) are not justification of these sanctions,” he wrote.

The appeal, which was denied by the investigators on Feb. 2, was a “last-ditch effort” to prolong or turn back the sanction, the man said in a phone interview.

“I messed up,” he said. “I wasn’t in a good place in my life in the least.”

The man, who moved all of his belongings out of University housing about a month ago, said “there were a lot of things (he) said” to make the woman feel better and feel less attacked.

Legally, he said he felt he could have fought, but “in terms of living with (himself)” found it best that he accepted the sanction.

“Too often, people see the situation as things that are either only right or only wrong or yes and no or black and white — very binary,” he said. “And they just aren’t resolved.”

He cited his and the woman’s history stemming from high school as part of the backstory but hesitated to explain, calling it a road hardly worth venturing down.

“I’m not trying to use my past or her past as an outlet,” he said. "I just think that when you speak to people about this, the knee-jerk reaction or the condition that is that, you know, that I’m a bad person, which I can’t even argue against, (but) things become a little more understandable (when you) see the whole story.”

His chance to tell the whole story will “probably not” happen at the University as far as he can see, he said.

He said he doubted whether he would return to the University when his suspension ended, transfer to another college or proceed in his military career as a soldier currently in the Army Reserve.

“At this point in my life, (I’m) not really sure (what I want to do),” he said. “It’s not a whole lot left for me in a lot of places. I used to have lots of hope. But now I just — I don’t know.”

Back at school, the woman is getting ready to wrap up her college career.

Despite trying to remain positive after the incidents, her roommate, who asked for anonymity, said the woman has her bad days and has trouble sleeping.

“The idea of him being on campus makes me sick to my stomach,” the woman said. “But going through a process where nothing will come of it seems so daunting and so unnecessary. Like I want to fight for this in any way I can but I have no case.”

She said the case will most likely end with University investigators because she questions the efficacy of the legal system, even more so after her experience with University police. As of publication time, she had not issued a formal complaint with the University about the handling of her case.

She said she is also tired of being blamed by the police and University investigators for being a victim.

“It’s the issue of being the perfect victim,” she said. “Because I had consensual sex with him in the past, I was no longer a valid victim. So it’s also the idea of being in an alleyway — you don’t know someone. It has to be a stranger. It probably has to be a black man who already has convictions. There are certain implications for what the rapist has to be and what the rape victim has to be as well.”

Most of all, she said she is stunned that Rutgers chose to suspend a student who openly confessed to sexually assaulting a student instead of expelling him.

“I want a school that will take care of me,” she said. “That’s what I wanted, and they did not do that.”

Katie Park is a School of Arts and Sciences junior majoring in political science and journalism and media studies. She is the News Editor at The Daily Targum. Follow her on Twitter @kasopar for more stories.

Editor's note: A previous version of this story said students choosing to go through the University process in a case of misconduct could not simultaneously pursue a separate criminal charge.