BEZAWADA: Take add/drop period failures as opportunity

If you are a Scarlet Knight, it is pretty much guaranteed that you have experienced the terror of add/drop week. If you have not, you eventually will. Checking your Internet connection 7 million times, all of your index numbers ready, itching to snap your bed-frazzled hair, waiting with bated breath for WebReg to open — in that moment, you forget about niceties and all your friends. You might think "If I don’t get that calc class, I swear to god ..." But you can fill it in. It is one of the beauties of being a 21st-century college student.

Since I am a first-year student, when the first semester arrived, panic hit me hard. Somehow, I latched onto most of the classes required for my major. But I needed a Byrne seminar to fulfill a program requirement. I had my eyes on “Language Games and Talking Heads.” It snagged my interests like free food and merchandise lures students. The seminar combined linguistics, psychology and communication, analyzing the mind games people subconsciously play as they talk with each other. But of course, as life always is, the one course I wanted could not fit into my schedule.

Naturally, disappointment weighed down on me. The only other seminar that somewhat interested me and fit into my schedule was “Discovering Friendship in Japanese Pop Culture, Cinema, and Text: A Cross-Cultural Inquiry.” I reluctantly enrolled in it, my thoughts lingering on language games even as I walked into my first class.

Turns out, I loved it.

As a class, we did exactly what the title said — analyze Japanese movies and books for various themes of friendship. The material was inspirational, the discussions enlightening. But my biggest gain from the class, ironically, was friendship itself. I connected with so many other students out of a shared interest in Japan, and conversing with them is always a highlight of my day. As the seminar draws to a close, I can only hope our friendship will continue.

The course was so enjoyable that I had completely forgotten about the Language Games seminar until I started writing this article.

Sometimes, the idea of doing something we do not know we like seems daunting until we actually try it. That is normal. In fact, there is an entire area of study dedicated to it. In microeconomics, there is a concept known as the “opportunity cost” — the true cost of making a choice is what you must give up in order to do it. Whenever a decision is made, there is a sacrifice. And when a sacrifice is involved, an implied risk of irreversible failure is the result. But if we want to grow as wise people who have experienced how to get up and move on, those decisions must happen. In behavioral economics, there is something known as “status quo bias,” when people don’t decide at all to avoid any risk of loss. What they do not realize is choosing not to choose is a choice itself.

Because the thing is, along with that possibility of regret, there is a chance of success, no matter how small. Our faith in that hope — that things will get better — makes a critical difference. Even something as small as failing to get into the class you want still counts as a double-edged opportunity, one that shows what it feels like to lose, making you more empathetic and accustomed and forcing into you a clarity of mind so you can focus on other routes to your destination.

That is what entrepreneur Elon Musk, CEO of Tesla Motors and SpaceX, did. He could have used the easier path by taking a regular job in the auto industry. It was safe and guaranteed a fixed, decent salary. But he sacrificed safety for a highly risky field that only existed in his dreams: electricity-powered cars. It takes immense courage to believe in oneself so seriously, that your dreams can indeed become real. He risked homelessness, abandonment and endless failures until he finally succeeded in creating the two companies, and in the process, he revolutionized the auto industry and space travel. That one choice he made led him to change the world.

So many world leaders risked incredible losses to be who they are known now to history. Many more, like F. Scott Fitzgerald, author of "The Great Gatsby," suffered only a posthumous recognition. Yet numerous more are looked over by society altogether. But to me, the choices they made are not failures at all. They took themselves seriously and embarked on their own journeys. It is the people who do not make those choices at all, who instead decide to tread safely and regret not having done anything else, who truly suffer the most.

So as spring semester scheduling comes around, do not be daunted. Instead, take it as a challenge. Maybe you might not get your favorite class, but you will get a chance to find something entirely different. Who knows, maybe you will like it even more.

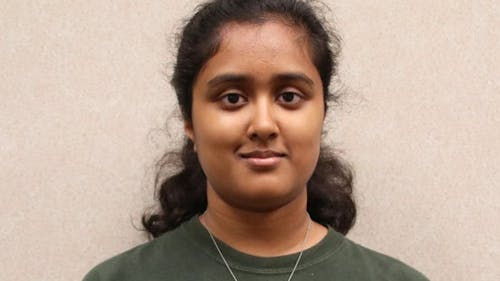

Sruti Bezawada is a Rutgers Business School first-year majoring in computer science and communications. Her column, “Traipse the Fine Line,” runs on alternate Thursdays.

*Columns, cartoons and letters do not necessarily reflect the views of the Targum Publishing Company or its staff.

YOUR VOICE | The Daily Targum welcomes submissions from all readers. Due to space limitations in our print newspaper, letters to the editor must not exceed 500 words. Guest columns and commentaries must be between 700 and 850 words. All authors must include their name, phone number, class year and college affiliation or department to be considered for publication. Please submit via email to [email protected] by 4 p.m. to be considered for the following day’s publication. Columns, cartoons and letters do not necessarily reflect the views of the Targum Publishing Company or its staff.