Cities learn to adapt to climate change, professor says

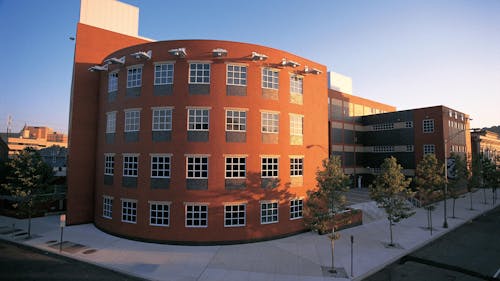

The Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy hosted the “Stuart Meck Memorial Lecture in Land Use Law and Affordable Housing” about plans and policies combined with social equity for climate change, on Tuesday, Nov. 12.

Stuart Meck was a professor within the Bloustein School, who died on April 2018.

“Stuart Meck was a really sharp guy and he is one of those irreplaceable people, we miss him and I miss him,” said Michael R. Greenberg, professor in the Edward J. Bloustein School and former interim dean.

The lecture was titled “Planning for Climate Change: Building Equity into Sustainable Urban Futures.” Equity is defined as being equitable, or dealing fairly and equally with all concerned, according to Merriam-Webster.

Cities are on the front lines of climate change, decisions are happening in cities to adapt to climate change and mitigate emissions and equity is important in making decisions, said Robin Leichenko, professor and chair in the Department of Geology and co-director of the Rutgers Climate Institute.

“It is kind of almost a daunting thing to think of how quickly our states are going to have to adapt and change with very rapid climate change coming on site and also this need to very rapidly transition our energy systems,” Leichenko said.

Leichenko showed a snapshot of the headline that “Climate change could end mortgages as we know it,” according to CBS. Planning for 30 years is starting to be questioned by investors, as for many cities they are already subject to a variety of environmental stresses like sea level rise and coastal erosion, Leichenko said.

New Jersey is also vulnerable to climate extremes in many ways, such as having had unnamed tropical storms cause flooding, Leichenko said. New Jersey is close to sea level and has trillions of dollars at risk.

“There is a deep inequality around who is causing climate change primarily and who is most vulnerable to climate change and sort of making the decisions around the future of how we are going to deal with climate change,” Leichenko said.

There was inequality within who could protect their home after Hurricane Sandy, where it cost $50,000 to raise a modest sized house on supports, Leichenko said. Hurricane Sandy is symbolic of a climate change event, but no single event can be attributed to climate change.

The communities that got bought out tended to be lower amenity, where higher amenity communities tended to reject buyouts, build dunes and took other measures to protect their communities, Leichenko said.

The Green New Deal speaks about creating jobs, just transitions for communities and workers and ensuring prosperity in legislative language, Leichenko said, without comment on whether the idea is good or not.

The Green New Deal forced equity and climate change researchers to catchup in their thinking to link economic justice and climate justice issues together, Leichenko said.

Climate change is a political issue, but the physical reality of change is impacting everyday city decisions such as managing the water system and road system, Leichenko said.

Three categories of equity include identifying communities needing resources and allocating resources, social economic political factors and processes such as structural racism and an inclusive decision-making process with community input, Leichenko said. Cities tend to be most experienced with the first category.

“These terms climate gentrification, green gentrification, were definitely present in the discussions and very much present in the minds of folks living in this neighborhood (Sunset park) that climate justice is for them,” Leichenko said. “It doesn’t look like the way we would think of climate justice in making sure we have sort of a clean future but making sure it also incorporates the jobs they have and the types of income they have.”

Community involvement is important, from the meeting deciding to do a mitigation plan to the planting of trees two years in the future, Leichenko said. Leading with equity helps make climate change efforts, plans and policy sustainable.

“If it’s not acceptable to the people who are making those changes and living with those changes it’ll be there for a little while, but it won’t really be enduring,” Leichenko said.

Addressing climate change also presents opportunities to make cities more livable and sustainable. The things that make cities energy systems more efficient and cleaner are largely the same as what needs to be done to prepare for and partly mitigate climate change, Leichenko said.

“One of the most powerful ways of thinking about taking action on climate change and thinking about motivating action in cities is to really remember that climate change is a huge opportunity,” Leichenko said.